In summer 2017, University of Iowa physicist Craig Kletzing learned NASA was giving him an initial $1.25 million to flesh out a proposal to study how solar winds interact with Earth’s magnetic fields — in hopes of better understanding space weather, including to what extent it might affect satellites and other aspects of everyday life.

Seven years later — after securing an additional $115 million from NASA to pursue the project in full, navigating delays through the pandemic and losing its leader in Professor Kletzing’s unexpected passing — the groundbreaking mission is nearing launch.

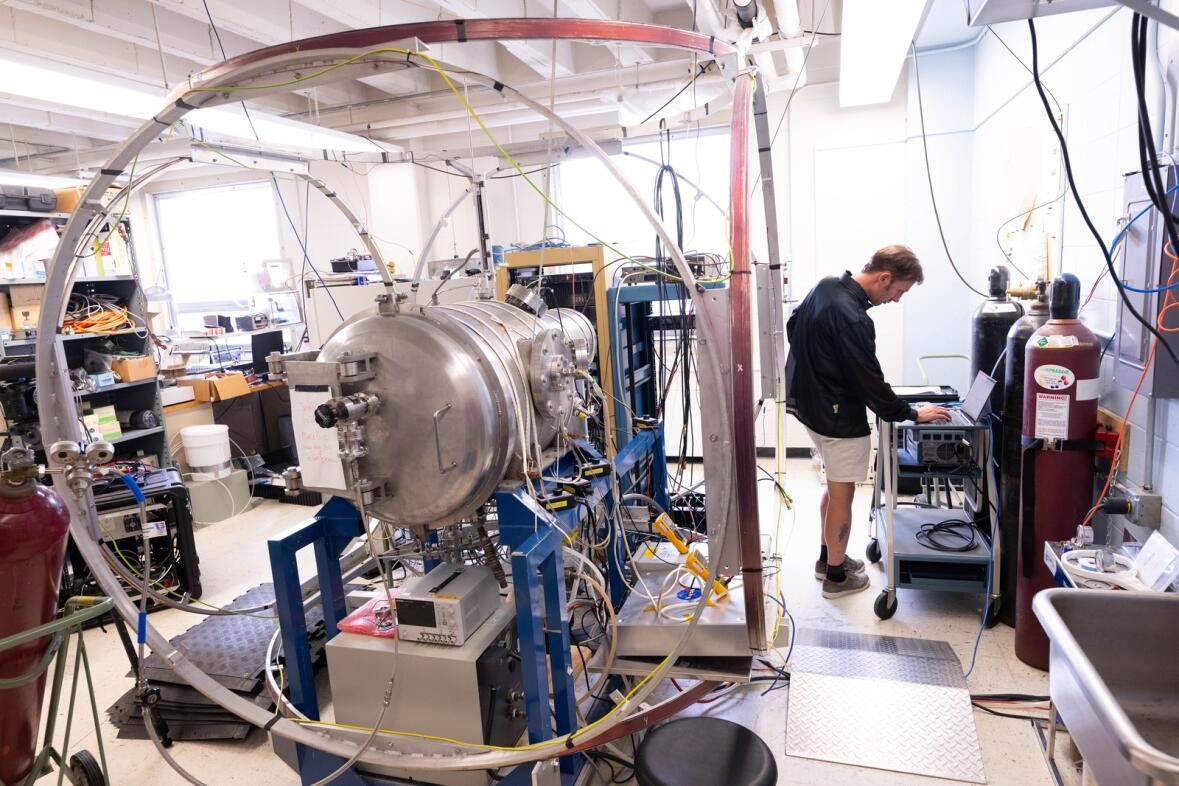

“All of the instruments are complete, were tested, brought to the University of Iowa, and then we put together what we call a suite of instruments,” David Miles, UI associate professor and principal investigator on the project, told The Gazette. The UI research team then shipped its instrument packages to the California-based spacecraft provider Millennium Space Systems, which announced this week it has finished building the pair of spacecraft that will fly them.

“And, as of last weekend and this week, the first of the two spacecraft is closed, meaning all the panels are on and it's buttoned up and it now goes through a testing campaign before it gets delivered to (California’s) Vandenberg Space Force Base for launch,” Miles said. “And the other one will be closed very shortly."

With a target launch date in April, Millennium — a Boeing company — now will undergo a monthslong series of tests for the mission called Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites, or TRACERS.

Space weather

As designed, TRACERS’ twin satellites will fly in tandem through the regions where Earth’s magnetic field opens over the north and south poles to capture data on how solar wind particles interact with our planet during a reconnection event. Magnetic reconnection is the “explosive transfer of energy” that happens when the solar wind first meets Earth’s magnetosphere. They cause the Northern and Southern Lights and can affect power grids and communication satellites.

“So as our society becomes more dependent upon technology — and, in particular, technology that is delivered from space, be that communication through something like Starlink, military sensing, GPS, which is the navigation that lets things like Google Maps navigate you — we become more and more sensitive to our ability to operate in near-Earth space,” Miles said.

“And one of the challenges to that is what's called space weather, which is basically these difficult-to-predict and rapid changes of the near-Earth environment.”

A solar wind and sudden enhancement of radiation can damage satellites and grind work to a halt on Earth. “So that business is called space weather, and the operational forecasting of space weather is a national priority,” he said.

NOAA — which produces traditional weather forecasts — now also is charged with producing space weather forecasts.

“So TRACERS isn't a space weather mission; we're not going to go do the space weather forecasting,” Miles said. “But TRACERS is enabling science — it's fundamental science — that underpins and enhances our ability to do things like space weather forecasting.”

Stressing the import of space weather, Miles said he expects it to become increasingly crucial as society becomes more reliant on near-Earth technology.

“What we have is actually very good, but its ability to look far into the future is very limited,” Miles said. “Our forecasts are much better on a 30-minute horizon than they are a two-day horizon.”

Part of the problem, he said, “is we need better observations.”

“There are parts of the physics that underpin how that system works that we just don't fully understand yet,” he said. “And that's really where TRACERS fits in.”

See also this Radio Iowa story about TRACERS.