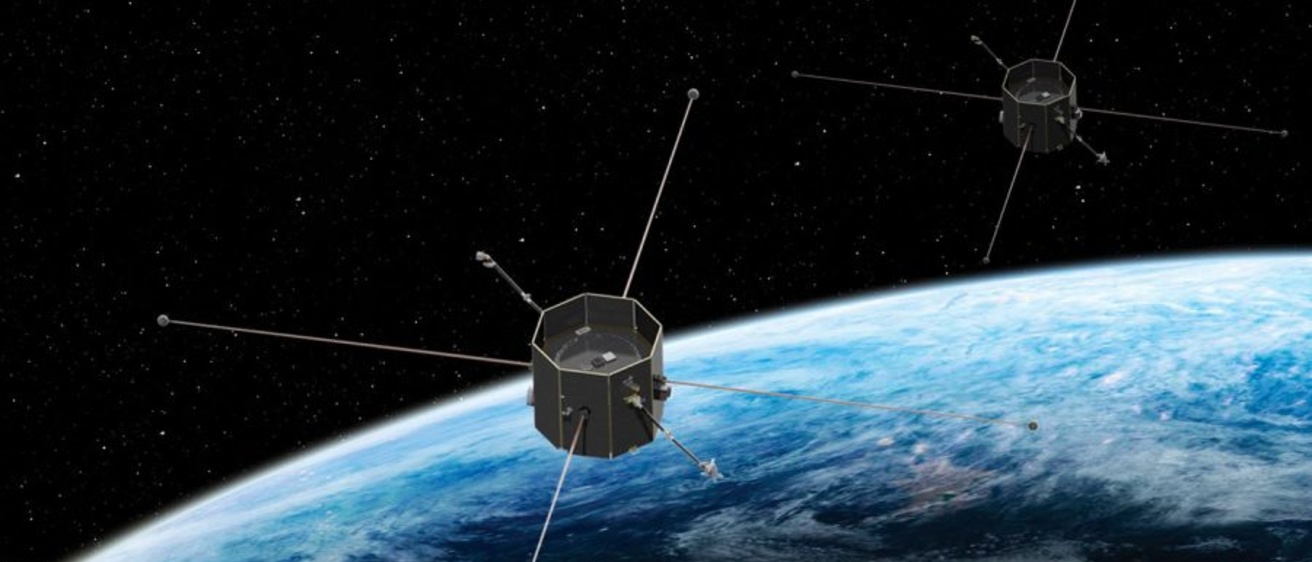

Scientists at the University of Iowa have passed a critical review by NASA and will soon begin building two satellites to study the sun’s effects on earth’s magnetosphere.

NASA approved a team of University of Iowa scientists to move to the next phase of their mission launching two satellites through the Earth’s northern polar cusp.

“We’re gearing up for some design reviews, and then we’ll be building the actual things that will fly in space,” said Craig Kletzing, the mission’s principal investigator and UI professor of physics and astronomy.

NASA provided UI investigators $115 million in 2019, the single largest amount of external funding in UI history at the time, for the Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites project, known as TRACERS.

The scientists have a launch readiness date of July 27, 2024, Kletzing said.

Scientists passed the Key Decision Point C phase recently, which focused on assessing their schedule and costs, he said, before passing it along to NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, which helps its associates develop satellites for probing.

“They want to make sure that you’re really ready to go,” Kletzing said. “It’s a key milestone.”

Without approval at Key Decision Point C, the team’s satellites might not have been able to launch or would have been delayed.

Jasper Halekas, UI associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, also emphasized the importance of this stage for the future of their mission.

“It’s a particularly important evaluation,” Halekas said. “This is really the gate that says, ‘Yes, your design is complete and you’re ready to start building the thing.’”

Kletzing said his team will study the Earth’s magnetosphere to eventually create better models that can predict disasters resulting from its contact with the sun. The magnetosphere is the region around the Earth that shields it from solar wind with its magnetic field.

“The process that [the satellite] is probing is what brings energy and momentum and mass in and around the Earth into what we call the Earth’s magnetosphere, which drives things like the Aurora Borealis and lots of space phenomena,” he said.

Kletzing referenced GPS and satellites as examples of what can be harmed by solar winds, a stream of particles from the sun that breach the Earth’s magnetosphere in a process called magnetic reconnection.

“Very large currents can be driven by this process that flow in the northern and southern polar regions, but they’re big enough that they can actually couple to things like power lines,” he said.

Kletzing cited the Quebec Blackout Storm of 1989, a solar event that caused a nine-hour power outage in the entire province, as one example of a disaster resulting from magnetic reconnection.

He also mentioned a more distant memory, the Carrington Event of 1859, a surge that blazed telegraph stations, even as it made auroral graphics for much of the world to see.

“If we can build better models that let us predict with more advanced warning what might happen, then you can say, ‘Hey, you guys should be paying attention,’” he said.

Kletzing’s team will repeatedly fly their satellites through the northern polar cusp, a consistent site of magnetic reconnection.

That the cusp is shaped like a funnel spiraling down to Earth is ideal, Halekas added.

“The cusp is this really unique location where we can observe the effects of that reconnection that happens much farther out,” Halekas said.

Scott Bounds, UI department of physics and astronomy associate research scientist and engineer and investigator on the mission, said the TRACERS mission continues the UI’s long tradition of building spaceflight hardware, initiated by James Van Allen, the late UI space scientist.

“It’s always very exciting after putting in a lot of hard work to design and build, to actually get the data back and see that your effort is important and has a result,” Bounds said. “The development of spaceflight transportation was kind of started here with Van Allen. I definitely want to see his legacy continue on.”

By Anthony Neri, News Reporter