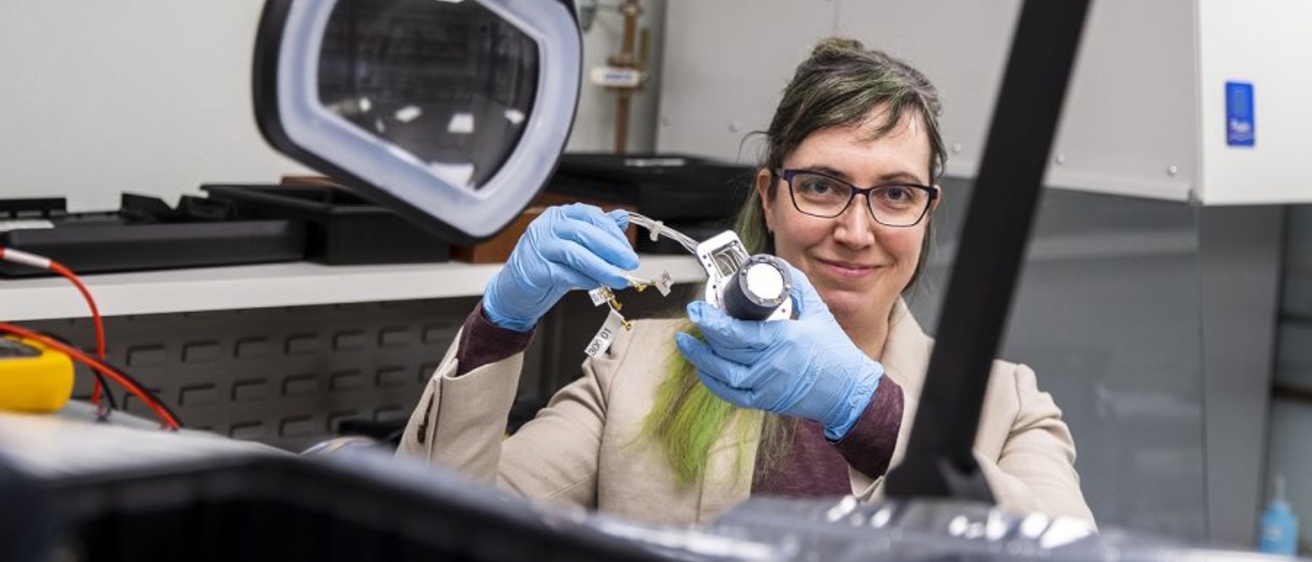

Allison Jaynes, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Iowa, is researching to detect specific mechanisms that conduct higher energies in Earth’s radiation belts.

A University of Iowa assistant professor is discovering specific mechanisms that conduct the higher energies in the Earth’s radiation belts through a NASA Heliophysics Supporting Research award.

Allison Jaynes, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the UI, received $84,000 from the University of California Los Angeles.

Jaynes said NASA ended a spacecraft mission in October 2019, the Van Allen Probes, that studied the radiation belts around Earth. The project is called “The role of local and radial diffusion in the multi-MeV electron acceleration,” and is expected to take three years.

“Some of the questions that UCLA and I wanted to answer with that mission still remain unanswered,” she said.

Jaynes said the NASA Heliophysics Supporting Research award will fund the data analysis of the Van Allen Probes spacecraft data.

“There’s a lot of things that can get disrupted if we have larger solar storms, or larger space weather events, which we have not had very much recently, because the sun has been a little bit quieter than it has in previous decades,” Jaynes said.

George Hospodarsky, UI research scientist and engineer, and Jaynes’ colleague, said a solar storm is a process where the sun is constantly shooting particles into space, called the solar wind.

On rare occasions, space tends to have coronal mass ejections, which is when energetic particles shoot up into space, Hospodarsky said. If these particles hit the earth’s magnetic field, it will vibrate at low frequencies.

“These particles also get trapped, which is one of the things we are trying to understand — exactly how this all works out. The radiation belts basically get much more intense, or they can actually get weaker,” Hospodarskysaid.

He said the radiation belts get either more energetic with more particles, or can lose some of the particles and rebuild over time.

Jaynes said her research study will try to figure out if high energy electrons are coming from within the radiation belt — a process that makes the changes from inside, compared to a process that brings in electrons from outside, into the location of the radiation belt.

Jaynes said the research is currently in a preliminary stage.

“With the UCLA group, we need to first see what happens when we put all this data into the Versatile Electron Radiation Belt (VERB) models,” she said. “From there, we can decide to do one thing or the other based on what the preliminary work shows.”

Hospodarsky said the VERB model is basically trying to model the radiation belt in three dimensions.

“Taking account of the particles and how things will change with different inputs and taking account of the different perimeters in space and how strong the solar wind is to predict how things are going to change in the future,” he said.

Kristine Sigsbee, UI associate research scientist and engineer, said Jaynes and her collaborators at UCLA are combining a computer model with actual satellite observations to better understand what causes space weather.

“I think her work is really exciting because she’s collaborating with researchers who have developed a computer model that helps predict radiation belt dynamics,” she said.

by Simone Garza, News Reporter